You must turn around

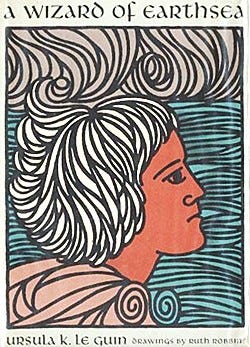

Thinking about A Wizard of Earthsea, a strange and special piece of young adult fantasy by Ursula K. Le Guin

“. . .where you should go, I do not know. Yet I have an idea of what you should do. It is a hard thing to say to you.”

Ged’s silence demanded truth, and Ogion said at last, “You must turn around.”

“Turn around?”

“If you go ahead, if you keep running, wherever you run you will meet danger and evil, for it drives you, it chooses the way you go. You must choose. You must seek what seeks you. You must hunt the hunter.”

Ged said nothing.

“At the spring of the River Ar I named you,” the mage said, “a stream that falls from the mountain to the sea. A man would know the end he goes to, but he cannot know it if he does not turn, and return to his beginning, and hold that beginning in his being. If he would not be a stick whirled and whelmed in the stream, he must be the stream itself, all of it, from its spring to its sinking in the sea. You returned to Gont, you returned to me, Ged. Now turn clear round, and seek the very source, and that which lies before the source. There lies your hope of strength.”

- From A Wizard of Earthsea, by Ursula K. Le Guin

A coming-of-age story can take many forms, but a classic variety features a young man gaining the strength and wisdom to assume the social responsibilities of an adult man. Telemachus gains the strength to drive away his mother’s suitors. Prince Hal gains the wisdom to cast Falstaff aside and accept his responsibilities as a royal heir.

A related variant, more common in contemporary storytelling, also features a hero learning to accept responsibility, but in order to do it, she must first recognize and accept her own true self. At Moana’s moment of crisis, when she lacks the strength to continue the quest to save her people, her grandmother’s spirit appears before her to ask: “Do you know who you are?” The question helps Moana see and accept the conflicts within her—the deep love for her people and the wild call of the sea—and in a spasm of self-actualization exclaims the only true (if somewhat literal) answer: “I am Moana!” The Princess Diaries features a similar journey: a teenage girl learns she is a princess, and, mistaking princesshood for a mask to be worn, has some fish-out-of-water romps in pretty dresses before deciding, tragically, that she wears it badly and must abdicate to her conniving cousins. But the act of choosing flips a switch inside her: she realizes that she will always be herself, whether she’s a princess or not, reimagines princesshood asan opportunity to share her best self—her generosity, her idealism—with the world, and races back to the ball to accept her crown wearing a sweatshirt and Doc Martens.

These stories often feature a moment of crisis, shortly before the moment of self-actualization, when the protagonist loses faith in the unconsidered-but-omnipresent self-identity of their youth. The confidence then returns, but now it’s more complex, more adult—it integrates their conflicts and doubts into a new more-deeply actualized confidence that will last them the rest of their lives. I love these stories, including the new Inside Out sequel, which featured the embodied emotions inside of its protagonist literally ripping out the simple, pure “Self” of childhood and growing a new, more complex one. I find these arcs to be both beautiful and relatable. The protagonist faces an external conflict—she becomes a princess, journeys across the ocean to return the heart of Te Fiti, goes to hockey camp, whatever—she tries to confront it using her existing toolkit, she fails, she tries to change herself to meet the challenge, she loses track of who she is, and then she has an encounter with friends or family that reminds her of what she’s forgotten, sparking a new identity that is rooted in the core self of her youth but adapted to the complexities of adulthood.

That moment of self-rediscovery has a deep emotional resonance for me. While these are stories about children, that renewal of confidence and secure identity, consistent across both past and future, is something that I fight for in adulthood. Seeing it compressed into a single triumphant moment moves me in the way that only great art can.

A Wizard of Earthsea (spoiler alert) features just such a triumphant moment. But how we get there is unlike any coming-of-age story I know. There’s no external quest to drive to the crisis point where the protagonist’s confidence falters. Instead, after a few chapters covering Ged’s childhood, we see him lose his confidence in a moment of supernatural trauma when, driven by hubris and jealousy, he attempts to call forth a spirit of the dead. The spirit appears, but along with it is a shadow, one that Ged spotted briefly in his youth, but who has not visited him since. Now the shadow emerges, corporeal and bestial, and mauls Ged before being driven away by the archmage—an old man who is killed by the effort. Ged is badly wounded, and his spirit is shattered.

Having stripped Ged of the confidence of youth, the story then follows a broken protagonist for the rest of the novel. Ged realizes that he’s not as talented as he thought, that he’s lived only for power without knowing what power is, and that what’s left beneath the pull to power is a only a deep well of fear and dread. Following Ged’s departure from school, the shadow pursues him, playing the role of the story’s villain. But it’s not really a proper villain. To Ged, the shadow is fear itself. In a world where the true essence of things are captured in their true names, the new archmage says it has no name. During its pursuit, the shadow sometimes loses track of Ged’s whereabouts, but the dread of its inevitability always remains, preventing the story from developing the the emotional variance that you’d normally experience in a pursuit-narrative.

Things drag on, subverting the classic coming-of-age narrative in young adult fiction. After the shattering of confidence should come the part where the friend or family-member appears to remind the protagonist who they really are, often within minutes or hours of the original moment of crisis. But Ged is chased for years before he gets his wise council, and when it finally comes, it does not cure his fear. Ged returns to Ogion, the quiet mage who gave Ged his name, whom Ged loved but left to pursue power. And Ogion tells him: “You must turn around.”

Ged’s particular trauma experience is unique and fantastical—he is, after all, destined to be the greatest archmage in all of Earthsea—but I wanted to share Ogion’s words because I think they are beautiful, if hard advice for anyone who finds themselves pursued by fear. The advice, in it’s generic form, is not original: don’t run from your problems; face them head on. So why do I love this moment?

When I read a favorite quote, there’s often an instant when I feel my body’s attention become complete: I click into place and feel myself adhere to the words: my thought, breath, and feeling become one with the text. Reading this quote, that happens right at the beginning: “It is a hard thing to say to you.” The speaker, Ogion, is a great mage who spends his days caring for his goats and casting no magic, but who, when an earthquake threatened the city of Gont, whispered kind words and calmed the earth’s rumble. What could a man who speaks to earthquakes find hard to say to a boy he loves?

So it is not the message, but the kindness of the old mage that touches me. The advice is so difficult, and his love for Ged is so great, that even the wisest hesitates to speak wisdom.

But I also wonder at the words Ogion chooses. One could phrase this advice very differently, with “turning” holding the opposite connotation: don’t turn and run; hold your ground and face your enemy. Resist the animal urge to flee. But that is not the advice Ged needs. We’ve seen him resist real and tangible fear: in an earlier chapter, Ged faces a powerful and angry dragon, and he feels that urge—the animal instinct to turn and run—but he holds his ground and masters the dragon by speaking its true name aloud. He can name the beast, and he defeats it.

But Ged does not know the shadow’s name. He is a brave boy with the strength to hold his ground—but against the shadow, his shadow, there is no ground to hold. The shadow is fear of a different kind: the kind that chases him before he can name it; the doubt and uncertainty that resides in his bones; the mistakes he’s made in the past, and the intrusive, inescapable thought that everything he gains is a thing he will lose. Depression, regret, and loss of self—the deepest pit.

Against this kind of fear, what is there to do but run? What else is there to do but just keep moving, seek distraction, ignore the whispers—strive to achieve so much that our accomplishments outpace our doubts and the fear of loss. What else is there to do?

It is a hard thing to say to anyone, myself included, but you must turn around.